|

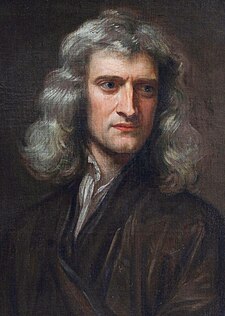

| Sir Isaac Newton |

Sir Isaac Newton FRS (4 January 1643 – 31 March 1727 [OS: 25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726])[1] was an English physicist, mathematician, astronomer, natural philosopher, alchemist, and theologian who is considered by many scholars and members of the general public to be one of the most influential people in human history. His 1687 publication of the Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (usually called the Principia) is considered to be among the most influential books in the history of science, laying the groundwork for most of classical mechanics. In this work, Newton described universal gravitation and the three laws of motion which dominated the scientific view of the physical universe for the next three centuries. Newton showed that the motions of objects on Earth and of celestial bodies are governed by the same set of natural laws by demonstrating the consistency between Kepler's laws of planetary motionand his theory of gravitation, thus removing the last doubts about heliocentrism and advancing the Scientific Revolution.

Newton built the first practical reflecting telescope[7] and developed a theory of colour based on the observation that a prism decomposes white light into the many colours that form the visible spectrum. He also formulated an empirical law of cooling and studied the speed of sound.

In mathematics, Newton shares the credit with Gottfried Leibniz for the development of the differential and integral calculus. He also demonstrated the generalised binomial theorem, developedNewton's method for approximating the roots of a function, and contributed to the study of power series.

Newton remains uniquely influential to scientists, as demonstrated by a 2005 survey of members of Britain's Royal Society asking who had the greater effect on the history of science and made the greater contribution to humankind, Newton or Albert Einstein. Royal Society scientists deemed Newton to have made the greater overall contribution on both.[8]

Newton was also highly religious, though an unorthodox Christian, writing more on Biblical hermeneutics and occult studies than the natural science for which he is remembered today. The 100 by astrophysicist Michael H. Hart ranks Newton as the second most influential person in history (below Muhammad and above Jesus).

Sir C.V.Raman

Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman, FRS (Tamil: சந்திரசேகர வெங்கடராமன்) (7 November 1888 – 21 November 1970) was an Indian physicist and Nobel laureate in physicsrecognised for his work on the molecular scattering of light and for the discovery of the Raman effect, which is named after him. Raman had significant contributions to the quantum photon spin, acousto-optic effect, acoustics of Indian musical instruments.

Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman, FRS (Tamil: சந்திரசேகர வெங்கடராமன்) (7 November 1888 – 21 November 1970) was an Indian physicist and Nobel laureate in physicsrecognised for his work on the molecular scattering of light and for the discovery of the Raman effect, which is named after him. Raman had significant contributions to the quantum photon spin, acousto-optic effect, acoustics of Indian musical instruments.

On February 28, 1928, through his experiments on the scattering of light, he discovered the Raman effect. It was instantly clear that this discovery was an important one. It gave further proof of the quantum nature of light. Raman spectroscopy came to be based on this phenomenon, and Ernest Rutherford referred to it in his presidential address to the Royal Society in 1929. Raman was president of the 16th session of the Indian Science Congress in 1929. He was conferred a knighthood, and medals and honorary doctorates by various universities. Raman was confident of winning the Nobel Prize in Physics as well, and was disappointed when the Nobel Prize went to Richardson in 1928 and to de Broglie in 1929. He was so confident of winning the prize in 1930 that he booked tickets in July, even though the awards were to be announced in November, and would scan each day's newspaper for announcement of the prize, tossing it away if it did not carry the news. He did eventually win the 1930 Nobel Prize in Physics "for his work on the scattering of light and for the discovery of the effect named after him. He was the first Asian and first non-White to receive any Nobel Prize in the sciences. Before him Rabindranath Tagore (also Indian) had received the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Jagadish Chandra Bose

Jagadish Chandra Bose, CSI,[2] CIE,[3] FRS (Bengali: জগদীশ চন্দ্র বসু Jôgodish Chôndro Boshu) (30 November 1858 – 23 November 1937) was an outstanding Indian polymath: a physicist, biologist, botanist, archaeologist, as well as an early writer of science fiction.[4] He pioneered the investigation of radio and microwave optics, made very significant contributions toplant science, and laid the foundations of experimental science in the Indian subcontinent.[5] IEEE named him one of the fathers of radio science.[6] He is also considered the father of Bengali science fiction. He was the first person from the Indian subcontinent to receive a US patent, in 1904.

Born during the British Raj, Bose graduated from St. Xavier's College, Calcutta. He then went to the University of London to study medicine, but could not complete his studies due to health problems. He returned to India and joined the Presidency College of University of Calcutta as a Professor of Physics. There, despite racial discrimination and a lack of funding and equipment, Bose carried on his scientific research. He made remarkable progress in his research of remote wireless signaling and was the first to use semiconductor junctions to detect radio signals. However, instead of trying to gain commercial benefit from this invention Bose made his inventions public in order to allow others to further develop his research.

Bose subsequently made a number of pioneering discoveries in plant physiology. He used his own invention, the crescograph, to measure plant response to various stimuli, and thereby scientifically proved parallelism between animal and plant tissues. Although Bose filed for a patent for one of his inventions due to peer pressure, his reluctance to any form of patenting was well known.

He has been recognised for his many contributions to modern science.

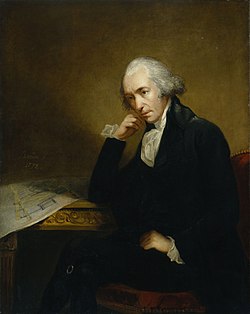

James Watt

James Watt, FRS, FRSE (19 January 1736 – 25 August 1819)[1] was a Scottish inventor and mechanical engineer whose improvements to the Newcomen steam engine were fundamental to the changes brought by the Industrial Revolution in both the Kingdom of Great Britain and the world.

While working as an instrument maker at the University of Glasgow, Watt became interested in the technology of steam engines. He realised that contemporary engine designs wasted a great deal of energy by repeatedly cooling and re-heating the cylinder. Watt introduced a design enhancement, the separate condenser, which avoided this waste of energy and radically improved the power, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness of steam engines. He developed the concept of horsepower.[2] The SI unit of power, the watt, was named after him.

Watt attempted to commercialise his invention, but experienced great financial difficulties until in 1775 he entered a partnership with Matthew Boulton. The new firm of Boulton and Watt was eventually highly successful and Watt became a wealthy man. In retirement, Watt continued to develop new inventions though none were as significant as his steam engine work. He died in 1819 at the age of 83.

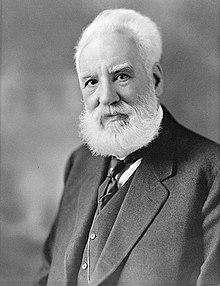

Alexander Graham Bell

As a child, young Alexander Graham Bell displayed a natural curiosity about his world, resulting in gathering botanical specimens as well as experimenting even at an early age. His best friend was Ben Herdman, a neighbour whose family operated a flour mill, the scene of many forays. Young Aleck asked what needed to be done at the mill. He was told wheat had to be dehusked through a laborious process and at the age of 12, Bell built a homemade device that combined rotating paddles with sets of nail brushes, creating a simple dehusking machine that was put into operation and used steadily for a number of years.[10] In return, John Herdman gave both boys the run of a small workshop within which to "invent".[10]

From his early years, Bell showed a sensitive nature and a talent for art, poetry and music that was encouraged by his mother. With no formal training, he mastered the piano and became the family's pianist.[11] Despite being normally quiet and introspective, he reveled in mimicry and "voice tricks" akin to ventriloquism that continually entertained family guests during their occasional visits.[11] Bell was also deeply affected by his mother's gradual deafness, (she began to lose her hearing when he was 12) and learned a manual finger language so he could sit at her side and tap out silently the conversations swirling around the family parlour.[12] He also developed a technique of speaking in clear, modulated tones directly into his mother's forehead wherein she would hear him with reasonable clarity.[13] Bell's preoccupation with his mother's deafness led him to study acoustics.

His family was long associated with the teaching of elocution: his grandfather, Alexander Bell, in London, his uncle in Dublin, and his father, in Edinburgh, were all elocutionists. His father published a variety of works on the subject, several of which are still well known, especially his The Standard Elocutionist (1860),[11] which appeared in Edinburgh in 1868. The Standard Elocutionist appeared in 168 British editions and sold over a quarter of a million copies in the United States alone. In this treatise, his father explains his methods of how to instruct deaf-mutes (as they were then known) to articulate words and read other people's lip movements to decipher meaning. Aleck's father taught him and his brothers not only to write Visible Speech but also to identify any symbol and its accompanying sound.[14] Aleck became so proficient that he became a part of his father's public demonstrations and astounded audiences with his abilities in deciphering Latin, Gaelic and evenSanskrit symbols.